Originally published on pnnl.gov, July 29, 2020.

RICHLAND, Wash.—Electric vehicles are coming—en masse. How can local utilities, grid planners and cities prepare? That’s the key question addressed with a new study led by researchers at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy’s Vehicle Technologies Office.

“While we don’t know exactly when the tipping point will happen, fleets of fast-charging vehicles are going to change how cities and utilities manage their electricity infrastructure” said Michael Kintner-Meyer, an electrical systems engineer in PNNL’s Electricity Infrastructure group and the study’s lead author. “It’s not a question of if, but when.”

The study, published today, integrates multiple factors not evaluated before, such as electric trucks for delivery and long haul, as well as smart EV charging strategies.

Transportation electrification is coming

According to EV Hub, about 1.5 million EVs, mostly cars and SUVs, are currently on the road in the U.S. PNNL researchers evaluated the capacity of the power grid in the western U.S. over the next decade as growing fleets of EVs of all sizes, including trucks, plug into charging stations at homes and businesses and on transportation routes.

For their study, the authors used the best available data about future grid capacity from the Western Electricity Coordinating Council, or WECC. The analysis revealed the maximum EV load the grid could accommodate without building more power plants and transmission lines.

The good news is that through 2028, the overall power system, from generation through transmission, looks healthy up to 24 million EVs—about 9% of the current light-duty vehicle traffic in the U.S.

However, at about 30 million EVs, things get dicey. At the local level, issues may arise at even smaller EV adoption numbers. That’s because one fast-charging EV can draw as much load as up to 50 homes. If, for example, every house in a cul-de-sac has an EV, one power transformer won’t be able to handle multiple EVs charging at the same time.

.

Source: https://www.pnnl.gov/news-media/influx-electric-vehicles-accelerates-need-grid-planning

Smoothing out the duck curve

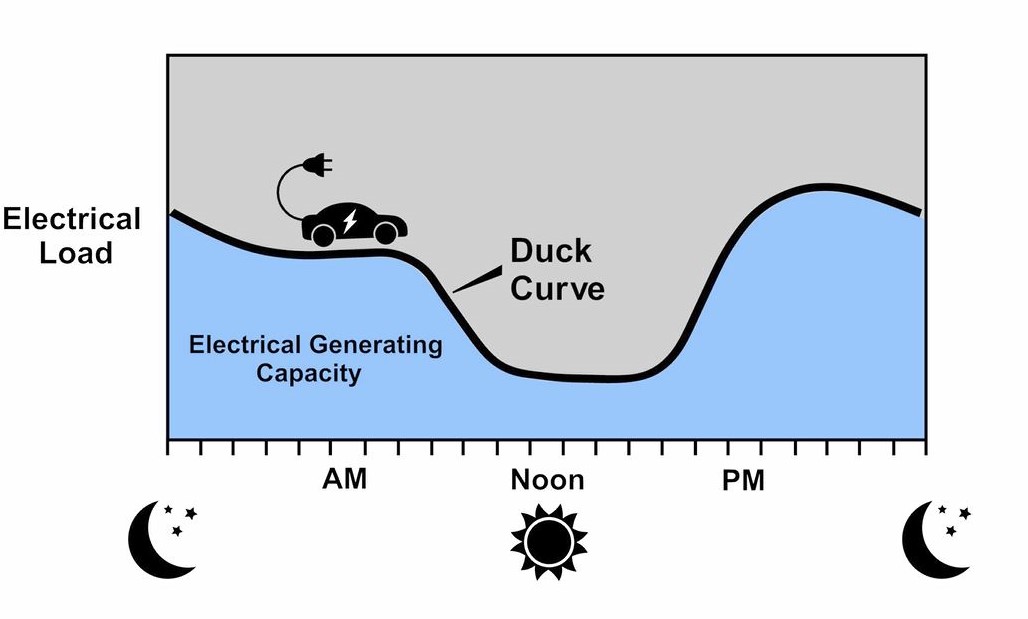

As detailed in the report, current grid planning doesn’t adequately account for a mass influx of EVs. That omission exacerbates an already stressful situation—the dreaded duck curve.

The duck curve is a 24-hour profile of load on the power system, and usually occurs in areas with a lot of photovoltaic—or solar—rooftop installations. The curve is based on moderate load in the morning, low load during the day when solar units feed electricity into the grid, and high load at night as people get home from work and the sun goes down.

When demand spikes, voltage plummets. This severe swing is hard on system operations that weren’t designed to flip on and off like a light switch. And with more EVs plugging in to charge in the evening, the ramp-up becomes even steeper and drives up electricity costs.

Smart charging strategies—avoiding charging during peak hours in the morning and early evening—can smooth out demand peaks and fill in the duck curve, according to the study. The approach has two upsides. First, it would take advantage of relatively clean solar power during the day. It would also reduce or eliminate the sharp ramps in the evening when solar power fades and other sources kick in to make up the difference.

Plausible scenarios emphasize need for planning

Building from the WECC data, the team developed and modeled plausible scenarios for 2028. The scenarios were vetted with business leaders and included a mix of light- (passenger), medium- (delivery trucks and vans) and heavy- (semis and cargo) duty vehicles on the road—the first time all three vehicle classes have been included in such an analysis. PNNL also developed a transportation model for freight on the road, with charging stations on interstate freeways every 50 miles for all three vehicle classes.

The scenarios included the evolution of the grid and its capacity at state and regional levels. The team focused on scenarios with the greatest potential for grid impacts.

Bottlenecks due to new EV charging appeared the most in areas of California, including Los Angeles, which plans to go all-electric with its city fleet by 2030. The pinch came from the growth of fast-charging cars and commercial fleets of electric trucks. These vehicles can draw 400 amps through a circuit for as long as 45 minutes, instead of the 15 to 20 amps pulled over 6 to 8 hours by most EVs today.

Dennis Stiles oversees PNNL’s energy efficiency and renewable energy research portfolio. He said fast-charging vehicles and integrating mobile loads—fleets on the move—are among the biggest challenges for planners today.

“They never really had to think about EVs before, but some cities are already looking into intelligent controls and other ways to modify their distribution systems and operations,” said Stiles. “The key is to figure out now how to avoid large capital outlays in the future. Adding a new transformer here and there is a lot different than a substation overhaul.”

Getting ahead of the curve

But the challenge isn’t limited to large areas like Los Angeles. Kintner-Meyer said smaller cities with limited resources need help planning for their charging infrastructure and hosting capacity. That’s the next step.

In a follow-on study, researchers will take a closer look at ways to integrate EVs into local and regional power distribution systems across the nation.

“We have the data and the method to run what-if scenarios,” said Kintner-Meyer. “With data from utilities about feeders and infrastructure, we can build out the models then hand it off so they can get ahead of the curve.”