Brendan Hannon, ERS, for Zondits

Welcome back to the second part of Zondits’ exploration of green roofs as an upcoming technology! Part 1 of the series provided a brief overview of the technology. In part 2, we answer the following questions:

If green roofs are so great, why aren’t they everywhere? And what industry trends may lead to the widespread adoption of the technology?

Those who recognize the benefits of green roofs are often frustrated by the technology’s slow rate of adoption in the United States; green roofs are still an oddity largely viewed as an amenity in the luxury housing market. But that may change soon! Cities across America are experimenting with a wide variety of carrots and sticks meant to spur the development of green infrastructure. In this article, Zondits explores past efforts to incentivize green roofs, dives into how specific cities are trying to go green (literally!), and looks into the future to see what collaborations need to happen to bring a green roof to a roof near you.

The Past

While the benefits of green roofs are well known, high upfront costs have prevented green roofs from becoming a common technology. Green roofs were an afterthought (if anything) during the design and construction of the majority of North America’s housing stock. Upfront costs for a green roof can be $10–$20 higher per square foot than asphalt roofs. As a result, many buildings that could benefit from green roofs are instead sitting under roofs that absorb heat, shed stormwater immediately, and need to be replaced more often.

The technology has also seen disappointing adoption rates as an efficiency measure; both the energy and water efficiency industries have targeted lower hanging fruits – measures that are easy to implement, quantify, operate, and finance. Energy efficiency programs have focused on more quantifiable actions with quick payback periods such as replacing lighting or adding controls to motors. Similarly, water utilities have used more conservative measures such as low-flush toilets and low-flow faucets to reduce stress on water distribution and treatment systems with great success.

As North America’s growing population continues to consume more energy and water, the need to implement efficiency measures to help supply meet demand has increased. Across the country, state regulators are demanding cleaner electric grids while the EPA is limiting the amount of stormwater that can be discharged into federal waters without treatment.

The Present

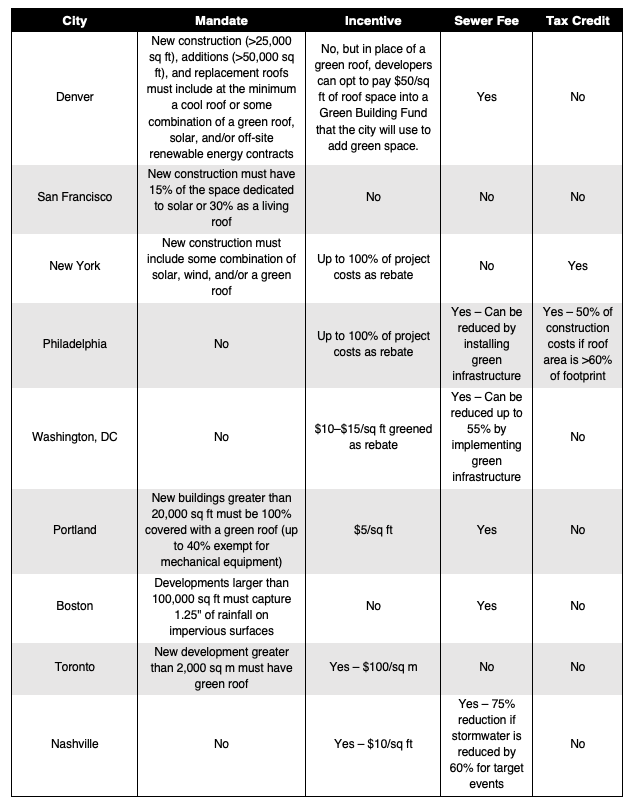

Recent years have seen an explosion of interest in green roofs across North America. This is largely driven by cities turning to green infrastructure instead of costlier alternatives such as new wastewater treatment plants to manage stormwater runoff. Successful examples include Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., two cities that have greened thousands of acres since beginning their green infrastructure programs. Other cities are eager to imitate their successes. In 2018, San Francisco and Denver both added laws requiring green roofs on new developments. Just this February, Atlanta issued an innovative environmental impact bond to finance $14M of green infrastructure projects. Still, no city has perfected the technology-implementation recipe to a point where the greatest benefits (i.e., neighborhood temperature reductions, avoidance of combined sewer overflow events) are realized. To date, cities are making use of a diverse toolbox of policies, incentives and fees to drive property managers towards green roofs. Mandates can drive adoption on new construction and incentives, and rebates and tax abatements can encourage retrofits of existing building stock. In addition to water fees, some cities charge sewer fees, a bill item that can be tied to the amount of impervious surface on a lot. These fees can be reduced by installing green infrastructure. The following table details measures nine North American cities are working to bring green roofs to their buildings.

These cities are leading the charge to deploy green roofs, but they each have a way to go before green roofs are as ubiquitous as their advocates might desire.

The Future

In the best case, the city of the future is greener, cooler in the summer, and surrounded by cleaner water. Green roofs have been strategically placed; the lower ambient temperatures reduce summertime cooling loads and, as a result, the local electric utility has retired the dirtiest peaker-plants, formerly turned on only during peak-cooling events in the summer. During moderate rainfall events, water is intercepted before being sent to a wastewater treatment plant. Sewers no longer overflow into local waterways, and the treatment plant operates at a lower capacity. The resulting decrease in electric demand from the water utility coincides with decreased solar production, enabling the electric grid to stay balanced on a mix of renewables even when the solar production drops. Populations of native pollinators rebound, the air is cleaner, and millions of city residents lunch on green roofs.

How do we get here?

Next Steps

The key to greening cities will be readily available financing for retrofits of existing buildings (in addition to mandates for new development). One key to that financing may be the availability of energy savings performance contracting, but that will only be available when the energy savings are well understood. Electric utilities have shown little interest in green roof technology, so the question of who will drive those innovations remains.

To find out how the green roof industry might reach that point, Zondits turned to Jason Lee from Quantified Ventures, the outcomes-based capital firm that worked with the City of Atlanta’s Department of Watershed Management to issue their recent environmental impact bond. We asked Jason if it would be possible to structure similar performance-based financing for energy efficiency.

“Outcomes-based financing vehicles like the Environmental Impact Bond (EIB) are a great financial instrument for things like green roofs. They are impactful but not yet standard interventions that require upfront capital. Municipalities such as D.C. and Atlanta have demonstrated leadership on select green infrastructure interventions with their EIBs, so layering in green roofs is quite possible. In an EIB, the repayment terms can be set according to a project’s monitored outcomes, thereby resulting in a cost of project capital that’s more efficiently tied to actual results. For example, a city’s repayment obligations to the impact bond’s investors might be higher or lower based on whether its investment in green roofs result in more or less energy savings and stormwater retention versus its projections. The EIB structure is also well-suited for interventions with multiple co-beneficiaries, as green roofs are.”

– Jason Lee, Quantified Ventures

Because the majority of incentives for green roofs have been driven by municipalities trying to address stormwater runoff, there has been little reason to quantify energy savings; as a result, knowledge about the energy efficiency benefits of green roofs has lagged behind our understanding of how they store stormwater. An EIB that includes energy efficiency savings as an objective would create an incentive to start measuring the energy savings using a more holistic approach (see this report on the New York City Department of Environmental Protection’s green infrastructure to understand types of energy savings that could be considered). The green roof industry is rapidly evolving as cities tinker with new strategies to encourage them. Zondits will be tracking the field with a focus on programs that seek to capture the energy efficiency benefits of green roofs.